By Christine Mangosing, Guest Writer for VINTA Gallery

As a graphic designer and a Filipino, I’ve long been fascinated with the Philippines’ unique take on both Art Nouveau and Art Deco — two design styles that originated in France around the turn of the century. In this segment, I’ll be focusing on Art Deco.

If you look closely amidst the modern skyscrapers and the cinder block buildings of the Philippines’ urban centres, there still remain a few majestic examples of Art Deco architecture, like the Far Eastern University campus and the Metropolitan Theatre in Manila. Outside the city, the opulent mansions of sugar and land barons exhibit distinct Art Deco influence in their architecture and ornamentation.

So how did Art Deco make it all the way to the Philippines?

First, let’s talk about what it is. Characterized by symmetrical lines, geometric shapes, stylized forms and rich colours, Art Deco celebrated the Machine Age, technology and progress. With international travel becoming more accessible and exposure to other cultures increasing, the artists who conceived of the Art Deco style were heavily influenced by the art of pre-colonial civilizations around the world. Combined with influence from the Cubism and Bauhaus movements, Art Deco resulted in a style that sharply contrasted the more classical styles that came before it. The style spread like wildfire and was quickly adapted across Europe, Asia and America.

Back in the Philippines, Manila was undergoing a major renovation under American rule. Spain’s 400 years in the Philippines had come to an end in 1898 after the Spanish-American war, which ended with Spain selling the Philippines to the US for $20 million dollars. There’s A LOT to that story and what came after, so I highly recommend looking into it. So, once America took over, they quickly got to work making significant changes in government, education, infrastructure and architecture. The Americans dismissed the Spanish colonial style already in place as “medieval” so they brought in city planners and architects to propose plans to change the urban landscape. To execute their plans, Filipino students were sent to architecture and design schools in the States and Europe.

These scholars, like Juan Arellano, Tomas Mapua and Juan Nakpil, returned from their studies ready to experiment with the styles and techniques they had learned, which included Art Deco. The patterns and motifs of the Art Deco style were ripe for adaptation to the Philippine’s tropical landscape. Using local, natural materials as their building blocks, the architects created stunning designs that maximized the flow of light and air and reflected their surroundings with stylized depictions of sunbursts, water, and tropical flora and fauna in the iron grill work, tiles, wood carvings and stained glass. Their adaptation of the style suited the climate and blended in seamlessly with the trademark capiz shell windows of the Spanish colonial style. It also bore a striking resemblance to indigenous art, particularly to the patterns found in the woven textiles of the T’boli and Yakan people in Mindanao and the Ifugao of Luzon. It is this aspect that strikes so much of my admiration for the period. That these pioneering artists were able to take a foreign influence and transform it into something that is so distinctly Filipino is a testament to the Filipino’s mastery of adaptation — a cultural trait that extends to so many other mediums including food, fashion, music and more.

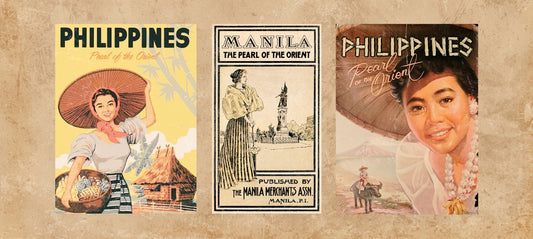

Sadly, many of the Art Deco homes and public buildings were destroyed in World War II when Manila served as the battleground for the Japanese and the Americans. Fortunately, the tenets of the style trickled down to furniture, embroidery and textiles, books and other printed ephemera — even cigarette labels, which bear some of the most beautiful examples of the era.

Tracing the history of Art Deco in the Philippines is not only a study of visual style but it also reveals the complicated layers of colonial history and the Filipino’s long fought journey towards independence and distinction.