By Amanda L. Andrei, Guest Writer for VINTA Gallery

I bought my black terno jumpsuit not knowing when or where I would wear it, just hoping that I would know the right time and place for those black butterfly sleeves to fly. For several months I stored it in my closet, letting it sleep amidst tissue paper in the same box in which it arrived.

I’m an artist — more specifically, a playwright — and I imagined that the first place I’d wear this outfit would likely be a big opening night or an LA theater community gala. Turns out I needed it for a more intimate gathering — just as celebratory as a big theater event, but much smaller in size and more vulnerable than I anticipated.

Recently, I’ve become a community archivist, shifting my artistic practice from the stage sets of theater to the storage bins of archives. According to UCLA’s Community Archives Lab, community archives are “independent memory organizations emerging from and coalescing around vulnerable communities, past and present.” They involve liberatory memory work — allowing these communities to enact their own timelines, exist independently, and animate the materials in the archive.

My community archive consists of my Filipina mother’s professional and personal correspondence from when she was a journalist in Eastern Europe, a Philippine Embassy press attaché in Romania, and a foreign correspondent in Washington, D.C. Over the decades, she amassed a wealth of photographs, papers, floppy disks, journalist’s notepads, letters, notes of encouragement, to-do lists, albums, cassette tapes, and more, items that have traveled across four continents and existed for decades — some for almost one hundred years.

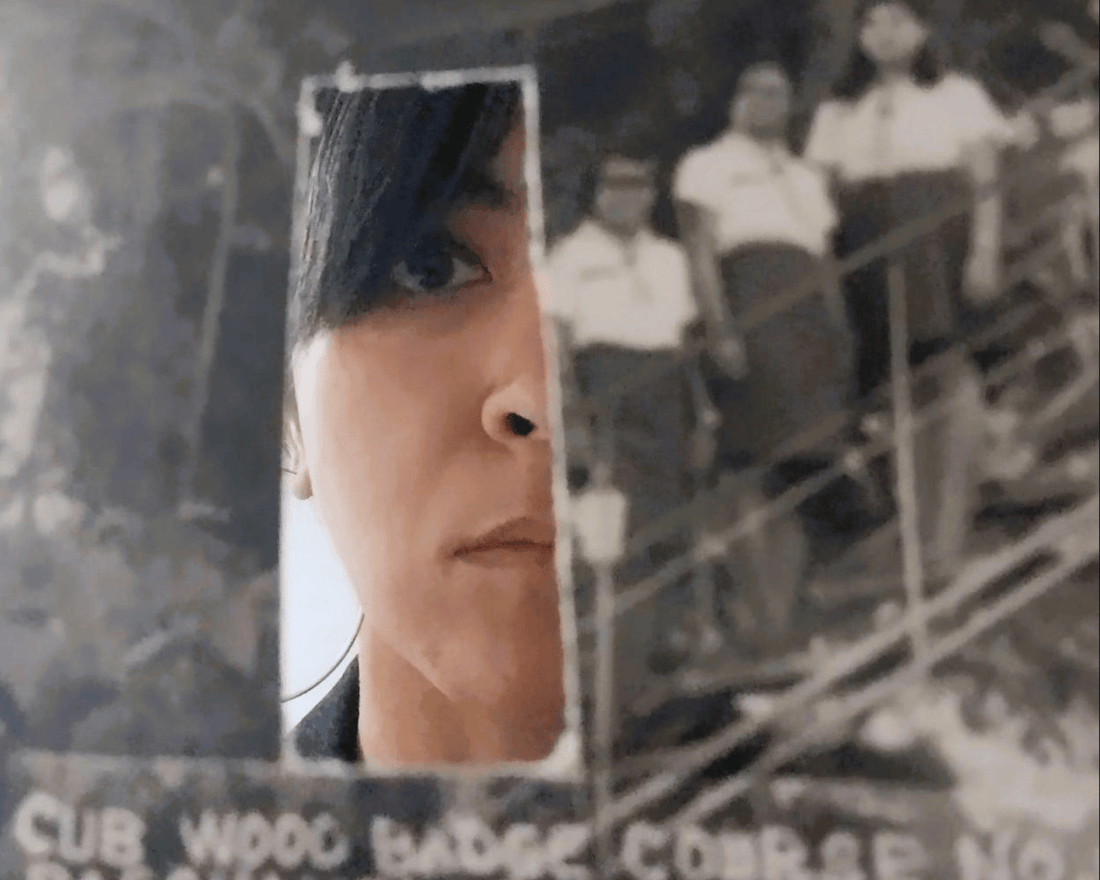

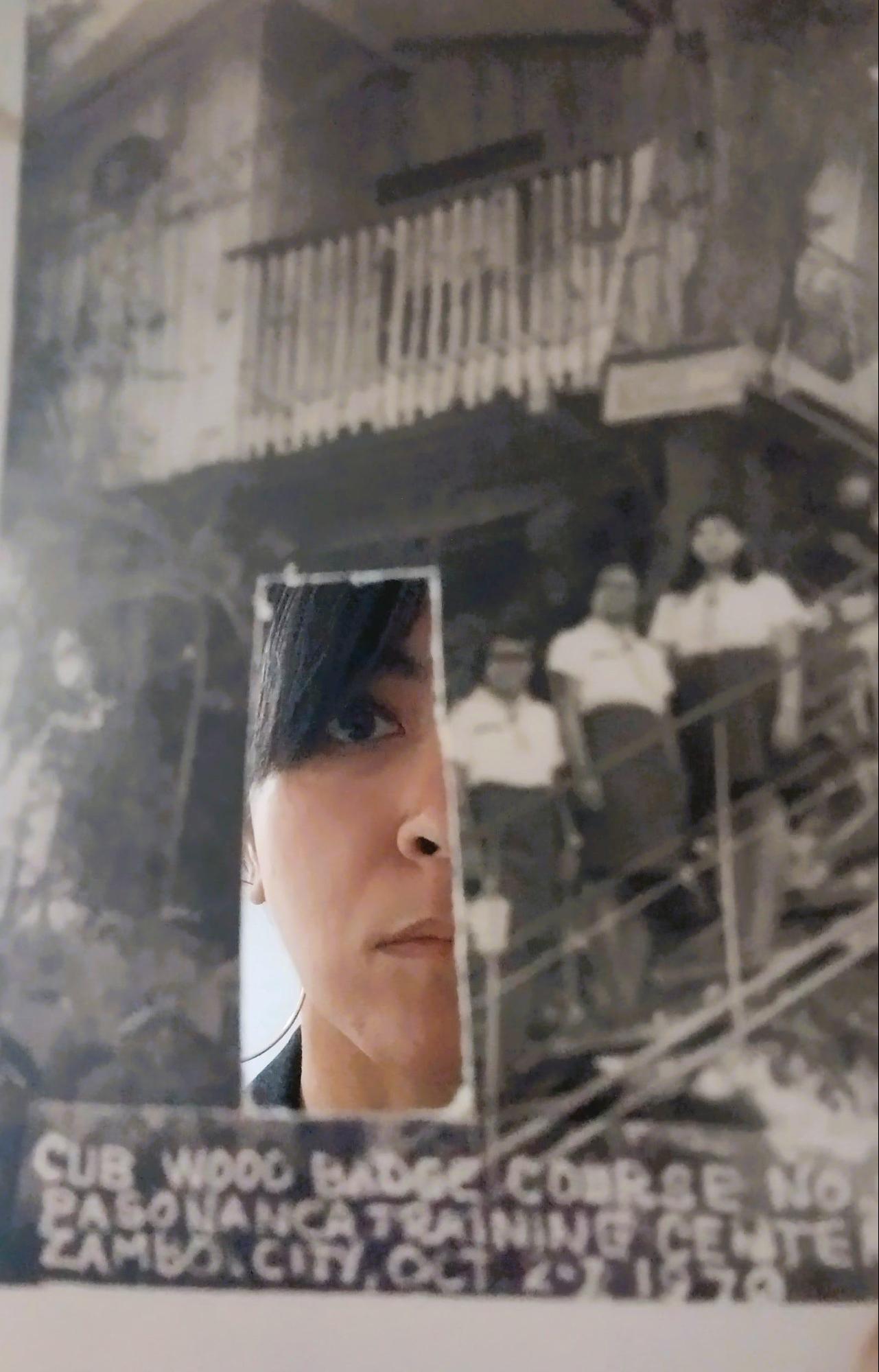

Check out some of these beauties:

In these photographs, I bear witness not just to the life of a globetrotting, badass Filipina mom, but to the small village in which she was raised, the student life of 1960s Manila, the boulevards of 1970s Bucharest, and the Washington D.C. of the 80s, 90s, and 2000s that I simply knew as home.

When I was sixteen years old, my mom unexpectedly passed away.

God. How do we mourn in the diaspora? How do we create devotional practices for our grief when we are far away from the homelands of our families?

After my mom died, I dressed in black for forty days. I began to do it yearly on her death anniversary. Then I didn’t want to remember her just through her death. I let my devotional practices fall away. I wanted to move out of mourning. I wanted to move into forgetfulness.

But your inheritance will find you, one way or another.

It has taken me nearly two decades to come back to her papers, volumes of heavy material that weighed down on me, a carapace I was born into and never asked for, but one that became as integral to my work as is being a child of immigrants, a Filipina, a Romanian, an American, a mother, an artist, a descendent, a future ancestor.

Her legacy. My inheritance.

I had to turn it into an artist project so that I could approach something so tender that it ached every time I touched it. I rented a space in Chinatown, LA, right between Broadway and Hill Street, where vendors line the streets in the late morning, selling fresh jackfruit and bunches of small bananas. When I work late evenings, I occasionally have a solo dinner at a nearby Filipino restaurant in Chinatown, mentally and emotionally processing all the photographs and their historical, personal weight.

I began dressing in black for the archives. It helped distance me from the emotional charge. I’m playing a part — I’m a stagehand, moving the furniture in the dark. I’m an usher, guiding people to their seats. Or I’m a funeral director, a professional mourner, making space for the ceremony of grief.

I began to invite people to the archives, mostly one on one. I found that this became a way to turn what would otherwise be a lonely project into one that gently moves between solitude and community. And when a friend and fellow community organizer suggested hosting a brunch in the space for Filipinx Artists, I knew it was time to bring out the black butterfly sleeves, to be publicly and visibly celebratory and proud. To animate the materials and liberate memory through elegance and potency.

I love this next photo for catching me off guard, for getting a stance that feels more real than when I posed for the camera. And I love that it comes from a history of other photographic portraits in my family, other high shoulders of lace and piña, of power and memory. Now you see me, these sleeves say. We have always been with you, you have always had mighty shoulders that hold you high. This fashioned cloth just lets the rest of the world know it.

The other day I found a photograph in the archives of my great-grandmother, my lolo’s mother. She stands before a painted backdrop of terrace steps, dark trees and river in the back, sunlight illuminating dark clouds. Hoop earrings, black hair pulled back, wide forehead, mouth pursed as if it misses a hand-rolled cigar to smoke. She wears a light-colored baro't saya: sheer and collarless camisa with big butterfly sleeves, scallop-edged alampay folding over her shoulders, tapis curving down and flaring out like a flowering trumpet. Embroidered motifs of dark ferns form proud columns on the sleeves, the alampay, all the way down the tapis to the floor. Her hands clasp a small dark handbag, drawn near her waist as if she just picked it up. I wonder what color everything is — the handbags and ferns, if they are a stark black, or perhaps a luscious deep blue.

I had never seen her before. The photo was dedicated to my lola, my mother’s mother, a woman who also died young, before I was born, and whose first name I carry as one of my middle names. She, too, lost her mother when she was young, barely a teenager. Too many women in my family have lost their mothers at an early age.

Maybe my grand-lola sensed this. Or maybe the photograph sensed this, the ink and paper and graphite animated by ancestral trust and descendant devotion, despite oceans and decades between us.

On the back of the photograph, my grand-lola wrote in pencil:

Pacakitkitaan yo canyac.

Toy inayo.

Graciously translated by Clem Montero from Ilocano to English, this says:

Your remembrance of me.

(from) Your mother.

This is the part of the story where you might expect to see the photograph for yourself. Instead, let me invite you to picture one of your own family members from long ago. How they might have wanted to be remembered. How they might have looked in beauty, in glamor, in power. Maybe their sleeves are voluminous and loud. Maybe they are quiet and homespun. Maybe there’s nothing but their own shoulders, proud and bare in the light of the sun and moon.

I remember you, Lola. I remember you, Mama. I remember you in your beauty and elegance, in your vulnerability and tenderness, all you who came before me and all who might come after me. Let this be a prayer for you too, beloved reader. May we always be graced with wings that know the right time to awaken, rise up, and soar. May we find ways to fill in the gaps of history with our beautiful, bold, courageous selves.

Amanda L. Andrei is a playwright, literary translator, theater reviewer, and community archivist based in Los Angeles. She writes epic, irreverent plays that center the concealed, wounded places of history from the perspectives of diasporic Filipina women. To learn more about her upcoming events and offerings, join her newsletter. You can also learn more about The Palangga Archives project here.