You may have seen it in old photographs of your mom or grandmother. You may have seen it in history books or random clips of Imelda Marcos visiting the White House in the ’80s. You may have seen it in Filipino beauty pageants or worn by Miss Universe Philippines 2018 Catriona Gray. The stunning, resilient, unabashedly opulent terno dress.

It can be referred to by so many names — Filipiniana dress, mestiza dress, Maria Clara dress — but one thing’s for sure: there is no other Filipiniana attire that represents the Philippines and the country’s stride towards modernity more so than the terno dress.

So what is a Filipiniana dress? What makes the Philippine terno so symbolic of a nation? Let’s take a quick journey with the dress.

THE HISTORY OF THE TERNO DRESS

The terno dress has been through it all. It evolved from the early Spanish colonial period (1700s), the revolution against Spain and the Philippine American War (Victorian Era), the American Colonial period, two World Wars, past the atomic age, through the authoritarian rule of the Marcos regime… and then some.

A quick history lesson: the terno traces its origins to the baro’t saya, traditional Filipino clothing worn by women, which consists of the blouse ("baro" or “camisa”), a folded rectangular piece of fabric worn over the shoulders (“pañuelo” or “fichu”), and a short rectangular cloth ("tapis") wrapped over top of a long skirt (“saya”). In the early Spanish colonial period, women from Luzon and Visayas wore these garments in layers of stripes and checkered patterns, which are a display of wealth.

By the 1860s, global trade and Hispanicization influenced the silhouette of the baro't saya. The upper garment, now called a “camisa” has become more complex with a pleated and straight pinned bodice that is delicately hand-embroidered, with voluminous bell or pagoda shaped sleeves. The camisa was usually made with pineapple fiber (piña) or muslin. The “saya” still floor length, has ballooned into a wide bell shape. The tapis is still present usually with a contrasting fabric pattern. Since Filipinos love nicknames, this ensemble was also called “traje de mestiza” (literally meaning mestiza dress, “mestiza” meaning people of mixed Filipino and any foreign ancestry). This ensemble was also affectionately named the Maria Clara dress, after the mestiza protagonist of the Philippine national hero, Jose Rizal’s controversial novel Noli Me Tangere in 1887. The dress itself was the metaphor for Maria Clara character’s modest, elegant and feminine traits in the novel.

Taken from Fashionable Filipinas: An Evolution of the Philippine National Dress in Photographs 1860-1960, curated and written by Gino Gonzales

To follow the evolution of the terno dress is to break down the Maria Clara dress of this period and its four main components. Here’s how it looked:

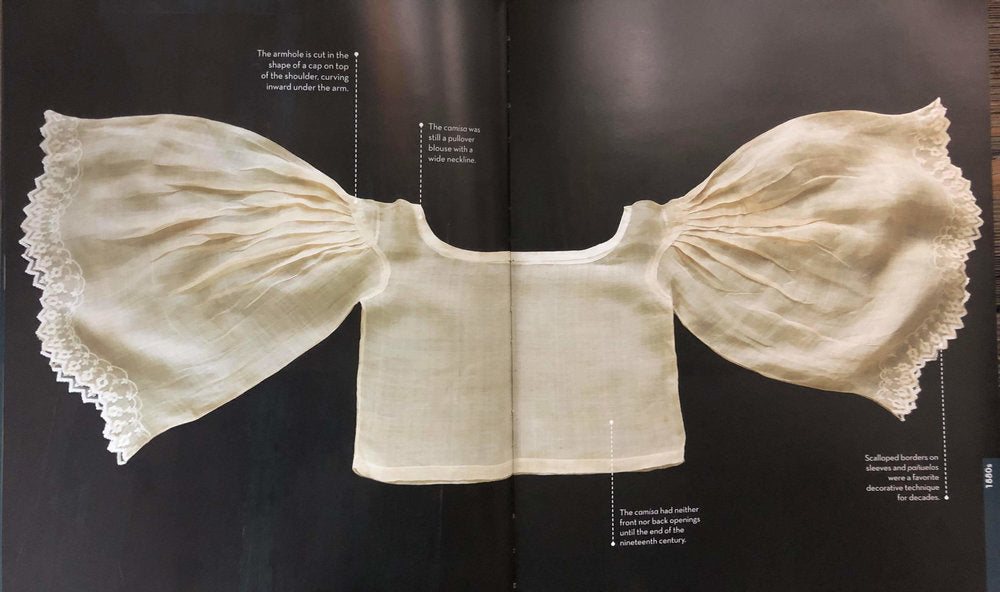

1. Camisa: a collarless blouse made with flimsy, translucent fabrics, such as piña. The camisa’s sleeves were shaped like angel wings or bells. The correct term for the sleeves of the camisa during the mid to late 1800s was a "pagoda," “on-trend” with Western silhouettes of the Victorian period.

2. Pañuelo: a piece of starched square cloth, usually made from the same material as the camisa, folded triangularly and worn like a big ruffle or collar over the shoulders. The pañuelo connoted modesty, as it was used to cover the nape and the upper body from the camisa's low neckline and translucency. It also doubled as an accent piece with its added embellishments and embroideries, with a pin or brooch securing it in place.

3. Saya: a skirt that hangs from the waist and covers the lower part of the body, reaching the floor. These were usually comprised either of single or double sheets, called "panels" or dos paños (Spanish for "two cloths").

4. Tapis: a knee-length over-skirt that hugs the hips. Tapis designs may be plain, or of contrasting pattern from the saya, and is usually made of opaque fabrics, such as muslin and the madras cloth.

From Álbum de Filipinas Publicación: , [ca. 1870]

During the American occupation, Filipino fashion started to change in favour of a more modern style. The traje de mestiza evolved to have bigger sleeves and a narrower, floor-length skirt with a long train (or “saya de cola”), replacing the full wide skirt of Edwardian fashion.

Fast forward to the 1920s and the wide sleeves were replaced by butterfly sleeves, which became a distinct element of the mestiza dress, with the big pañuelo also being reduced in size. Here’s where we start to see the emergence of the modern terno dress we see today — the word "terno" comes from the Spanish word “to match,” referring to a matching set of clothes made of the same fabric.

By the late 1940s, the terno's clothing meaning evolved into “a single piece dress with butterfly sleeves attached to it.” Ramon Valera, National Artist for Fashion Design in the Philippines, was credited for unifying the components of the baro’t saya into a single dress “with exaggerated bell sleeves, cinched at the waist, grazing the ankle, and zipped up at the back,” the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) said in a description of Valera on its website.

"Valera constructed the terno’s butterfly sleeves, giving them a solid, built-in but hidden support. To the world, the butterfly sleeves became the terno’s defining feature," it added. It is the terno dress that most Filipinos recognize today.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the terno saw, what many would say, its “golden era,” which coincided with the “golden era” of Philippine cinema. Films from those decades mostly featured leading ladies in gorgeous ternos. The terno was what your favourite movie star would wear, so in turn, it’s what all the fashionable women of the Philippines wore to all special events.

IMELDA MARCOS AND HER TERNO DRESS

“You know Imelda looked like a freaking queen to the rest of the world because of that dress. So let’s take that ‘queen dress’ dress away from her — take it back!”

In 2017, Miss Universe Philippines Maxine Medina stated in a video that the former First Lady of the Philippines Imelda Marcos invented the terno dress. Though she couldn’t have been more wrong, Imelda Marcos most definitely catapulted the iconic Filipiniana dress into the global stage with blazing determination.

Without forgetting the fact that the Marcos regime (1968-1986) was marked with blood, it is undeniable that part of their propaganda was to appear as though they were the King and Queen of the Philippines. And Imelda certainly played that Queen part very well, for the most part, thanks for the elegance and grace of the Filipiniana butterfly sleeves, earning her the nickname “The Iron Butterfly.”

It’s really no secret that it’s all in the sleeves. When it sits perfectly on the shoulders, the wearer simply oozes pure confidence, feminine fierceness and indescribable power.

Imelda Marcos in her terno dress alongside Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos, circa 1970s

The terno dress enjoyed international recognition because it was “Queen” Imelda’s uniform, deeming it a symbol of wealth and social status in the Philippines. Rumours were spread that Imelda would even tell the high society women that no one else could wear the terno dress but her.

After the 1986 Edsa Revolution, the struggle to keep the terno dress (and Filipiniana dressing in general) alive was real — people have now come to associate the terno with the controversial Marcos regime.

“[Imelda Marcos] killed that terno — she owned it so hard, and she had all the best designers and hand beaders all over the Philippines working for her, like going blind beading her ternos… It’s terrible that a Filipino traditional thing dies with two people that were hated.” — CAROLINE MANGOSING

No other fashion item strongly represents the rich Filipino history and culture than the terno dress. Though it’s been quite the battle to maintain its survival, slowly we’re beginning to see new Filipino designers coming up with and creating fresh new ways to revive the terno dress, with events like Ternocon, a multi-day terno design competition and convention in Manila, Philippines, focusing on the technical structure, design and patterns of the classic terno.

For many second generation Filipinos and the Filipino diaspora, especially in North America, it’s a continuing quest for identity and oftentimes a personal struggle to keep a close connection to their roots. For young people, there seems to be a thirst, a curiosity to hold on to and/or connect with a culture that’s undeniably theirs, whether or not they grew up in the Philippines. Fashion plays a huge role in creating those ties, allowing current and future generations to discover ways they can honour and express love for their own culture everyday.

Caroline Mangosing, founder and creative director of VINTA, remains an advocate of Filipino fashion, creating and designing high quality, modern Filipiniana dresses and clothing pieces that pay homage to Philippine fashion in history while pushing the boundaries of what Filipiniana attire should be.

The Tent Terno, VINTA’s first ever ready-to-wear terno and most popular.

As former executive director and founder of the Kapisanan Philippines Centre for Arts & Culture in Toronto, Canada, at the time, Caroline would receive many inquiries from Filipinos and Filipinas looking for a Filipino “costume.”

“I have a fashion background, so I thought, ‘I hate the idea of Filipino cultural clothing being costumes,’” Caroline says, adding we’re not dressing up as Filipinos for Halloween — we are Filipinos.

Caroline felt a deep need to introduce modern Filipiniana fashion in an urban city, especially among youth, educating and exposing them to this unique side of their culture. The VINTA Gallery Filipiniana Collection is inspired to bring back the chic and glamour of the past, but with the subtlety and high quality fit of modern custom made fashion. Filipiniana haute couture. Elegant meets badass.

The Iron Butterfly by VINTA Gallery

“The person I create for is someone who can bring Filipiniana into the fashion conversation,” Caroline says, in an interview with Preview Magazine. “I really just want to bring the idea of wearing Filipiniana outside of a Filipiniana dress code event, and my muse is that person who can rock Filipiniana for work, for brunch on a Sunday or for a cocktail party — not just a super formal Filipiniana dress coded event.”

Caroline Mangosing’s vision for VINTA from the beginning was to do away with the idea of Filipino clothing being simply a “costume.” She wanted to make fashionable, everyday Filipiniana clothing that anybody can fit into their regular wardrobe.

Another drive for Caroline in creating VINTA Gallery? Taking that terno dress “back” from Imelda Marcos, modernizing its elements and showcasing it to the world.

“It’s like, I want that dress back. I don’t want it to be for her. I want it to be mine, I want to wear it, I want to look that good. So it was that kind of idea — because it’s not hers. It’s all of ours.”

The direction of the terno in the 21st century is constantly in discussion among Filipino fashion experts and traditional and new designers alike. One thing’s certain: it’s not going anywhere.